Disarticulating CRAs

The 1960s was the decade of the Beatles, the civil rights movement, and the digitization of consumer finance. Banks discovered that they could move their records to computer terminals to slash administrative costs and make more money. It was a smash success. New revenue streams emerged, and banks began selling their own customers’ data on the open market. And why not? For the first time, a lender could call them up and say, “Bob from sales is looking to buy a new house and needs to confirm his monthly wages.”

There was just one problem: errors. Data was getting re-sold and re-keyed into computers with such speed that nearly half of all consumers reported inaccuracies when seeking approval for a new financial product. So the government took action. In October 1970, lawmakers rolled out an early draft of consumer data protections. The Fair Credit Reporting Act created fun entities called Credit Reporting Agencies (CRAs), which act as intermediaries between those holding consumer data and those requesting it—with one caveat. CRAs aren’t responsible for any errors in the data they share. After all, they’re just the middlemen. What could go wrong?

Acquire, store, sell. That’s the three-step process of CRAs, and it gives them outsized power. They profit through arbitrage—that is, pocketing the difference between the cost paid to a data “furnisher” and the price paid by a data “requester.” If this sounds like a scene from the movie Boiler Room, trust your instincts. But the practical implications are vast. The last time you applied for a credit card, a bank likely paid Equifax to run a report on your credit history. Of course, the data in that report came from somewhere else; Equifax is just storing it.

You’re likely thinking about that somewhere else part now. That somewhere else is your employer, your payroll provider, or your credit card company. The dragnet on consumer data is so vast that even Google participates by selling data from its workforce. In all likelihood, whatever system issued your last paycheck is doing the same. In fact, most employers and payroll providers have become addicted to the effortless, expense-free revenue—coupled with the indemnity from consumer complaints—that only a CRA can provide. And all of this is happening while the CRAs themselves are reporting large-scale security gaps.

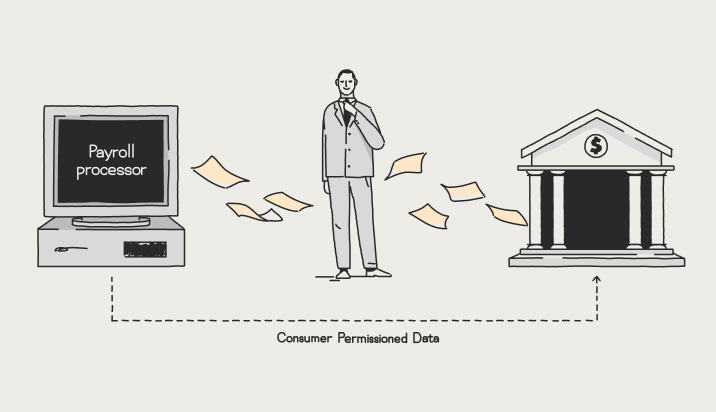

We got to this moment with noble means: to protect Bob’s data from inaccuracies and theft. But things have changed. Most importantly, we now have the internet at our fingertips. These days, consumers can access and share their own data on their own devices with just a few taps. And that means the gold standard of consumer protection has changed. It’s no longer about CRAs—or contracting out consumer data storage and sales—but about secure, permissioned data sharing, which requires working with consumers directly.

The shift to consumer-permissioned data is already happening in banking. If you’ve ever used a peer-to-peer (P2P) payments app like Venmo or an online banking app like Chime, an open banking API like Plaid is working behind the scenes to connect that app to your bank, so it can access your financial information. And it’s doing so with your fully informed permission—by having you sign into your bank account and actively opt in to sharing your data.

Now, it’s time to normalize that level of transparency and connectivity for income and employment data, another pillar of personal finance. Traditionally, there have only been a few ways to access a consumer’s income data. We’ve already mentioned most of them, and they’re not great. They either involve manual work for the financial service provider (contacting a consumer’s employer directly), manual work for the consumer (asking them to track down and scan a paper paystub or to upload a PDF), or going behind a consumer’s back to purchase their data from a CRA like Equifax.

The argument for using payroll connectivity platforms like Argyle could be a moral and ethical one. But it’s not. When we stream real-time, verified income and employment data straight from the source, prices go down, and accuracy goes up. CRA’s add an extra layer of cost, friction and pre-internet data speeds that are no longer in the best business interest of either financial service providers or consumers.

Welcome to the payroll connectivity revolution