How Hacking Harms Open Data Access

Since the dawn of data, the debate over who has ownership has vexed societies and their courts. From physical property to digital data, we continuously chase legal nuances to build morality and precedent around who holds claim to the original and who can copy it. The implications are real. Can you make a copy of a movie you purchased? Yes. Can you sell that copy? No. Can you sell the original copy you bought? Yes. As you can see, it’s complicated.

Let’s use photographs to illustrate. The camera owner takes a photo, which can be copied with the owner’s permission, and each photo holder is the owner of that copy. The complexity, when overlayed with internet-based data aggregation, is that copies are made at the time of viewing (data has to be “copied” to your phone to view that email). Alas, for the internet, data ownership is intertwined with data access.

The ownership quandary gets even more complicated when we pile on applications whose purpose is intercepting information between apps. Take, for example, a gig driver at a company like Uber or Lyft. The way drivers currently get each job is through automated dispatch. Driver’s parameters are mapped to a rider’s algorithmically, all to ensure utilization is balanced across the network. However, when we introduce privileged information (data like tips, order value or customer PII not ordinarily accessible to a driver), those with access to that data can gain an unfair advantage (think insider trading).

This data extraction is often referred to as “trip transparency.” It allows the driver to see distance, tip, merchant, customer, and earnings data that one’s peers cannot through the use of an intercepting code that hacks the communication stream between a gig app and gig dispatch. If that sounds like a misuse of English, trust your instincts. Now a driver with this privileged information knows what jobs will require the least amount of work for the highest amount of pay. There is a reason why platforms are not sharing this information with their workforce – it’s bad for business. Besides the apparent pitfalls, this process also touches upon the 3rd rail of data aggregation – who owns the data?

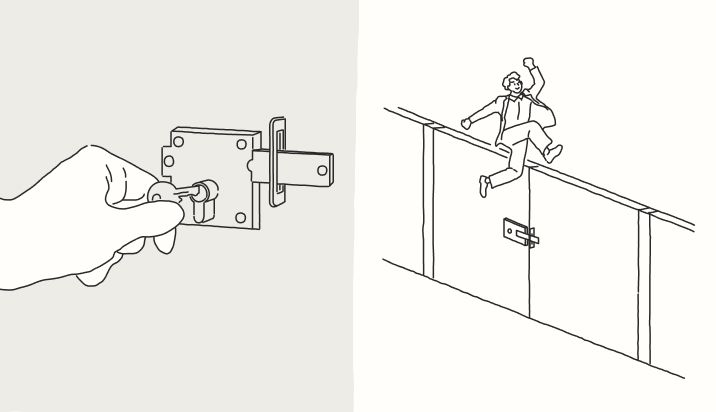

A recent Supreme Court ruling, Van Buren, refreshed the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act by defining hacking in a gate-open/gate-closed framework. Gates that are open for a user are ones they have the required access level to enter (i.e., login credentials). Closed Gates are ones that that same user does not have access to. Circumventing the gate is hacking.

My company, Argyle, which only transmits gate-open data (like paystubs and shifts) has seen its user base impacted by these nefarious actors as well. Further, the dignity of work is in question when workers are trying to optimize their earnings down to the minute like a computer. While Argyle can complete our functions for clients and consumers, I’m frustrated that bad actors have made the lives of 800,000+ gig workers harder – workers who use Argyle to facilitate insurance, gas, loans, and pay bills. An unruly minority has disrupted ordinary commerce, and a hard line needs to be drawn.

When we access systems appropriately, only using open gates, everyone benefits, and we significantly improve the lives of individuals who are most at risk. Open gates generate create needed morality on internet access, reduce fraud through verification, and create simplicity for consumers. For Argyle, in particular, this means real-time streaming data can help gig workers get a car loan, an apartment, a job, or pay early.

Hacking these systems may seem like a win over Goliath for a minority of folks that have the ability to access otherwise undisclosed information, but the greater good is only achieved when people copy a photo they truly have the ability to access.